I have had this article for quite a few years now, just sitting on the hard drive of my computer, waiting for an opportunity like this to share it. I consider it to be one of the most interesting blogs, rants (I shall leave it up to you to decide which one) that I have read. Its a long article but for those of you that have chosen the profession of being a University Lecturer I am sure you will find it an interesting read and quite amusing. So bear with it and enjoy – P.s. Don’t forget to leave a comment.

A surprising number of people express an interest in becoming a university lecturer and, knowing my background, ask me for advice on how to go about it. I was involved with university teaching — first as a PhD student, then as a research fellow, then as a lecturer — for about nine years, so I feel I have something to say about this. When people ask my advice on whether becoming an academic is a good idea, I’m never entirely sure what to say. Yes, there are some good things about an academic career, but at the same time there are some bad, scary things. The problem, it seems to me, is that people have an understanding of what the good things are likely to be when they join the profession, but they don’t find out about the bad, scary things until it’s too late. So I have written this outline of a university lecturer’s life in the hope that other people will we able to enter the profession — if they choose to do so — more fully informed than I was.

I gave up my job as a lecturer about three years ago, for a variety of reasons. Some were financial, some weren’t. On the whole I don’t regret becoming a lecturer, nor the effort it took to become one, but I don’t regret leaving either.

An interesting side-effect of the ’92 revolution was to narrow the gap in public perception between the `old old universities’, and the `new old universities’. With a new class of `new’ university, the original new (1950-1970) universities essentially became `new old universities’.

New universities (politely called `post-92 universities by people who work in them) inherited at least some of the administrative structures that dogged their polytechnic days.

Most polytechnics were run by Local Authorities, bodies whose responsibilities covered sports amenities, rubbish collection and parks maintenance, as well as education. They were not, it should be clear, specialists in the management of educational institutions. This meant, for example, that the Local Authority could attempt to gain economies of scale by buying the same computers for higher education laboratories as it would install on a swimming pool receptionist’s desktop. To this day, most new universities expect computing, maths, and physics students to use exactly the same computing facilities as, say, dance and drama students. That’s not to say there aren’t plenty of computer-literate dancers and actors, merely that their courses of study seldom require them to write software to calculate Fourier transforms or simulate the behaviour of protons in stellar collapse.

`Old’ universities, on the other hand, are predominantly run by committees of late-middle-aged gentlemen (or, just occasionally, ladies) whose main qualification to be looking after an annual budget of tens of millions of pounds is an international reputation in medieval verse or the military campaigns of the Athenian empire. Often in the `old old’ universities, these committees like to adopt quasi-classical names like `Senate’. With so many classical scholars involved it strikes me as odd that the fundamental irony of this name — that the original Roman Senate was an ineffectual figurehead for much of its existence — has so far escaped attention. At their most eccentric these administrative bodies have members with delightfully barmy titles, like `Senior Wrangler’, `Chief Blusterer’, or `Praelector’ (only one of these is made up). I find this all most satisfying, and very English.

Barmy as the administration of the old universities might be it is, on the whole, carried on by people who have a reasonable idea what a university is for: it’s for furthering scholarship, by means of teaching, research, and related activities. The new universities, however, are run by a different breed. Often business graduates or industrialists, they assess the success or failure of their institutions by their financial performance. For these administrators, the activities of their institutions have to be tuned to generating the largest financial return. To be fair, it has to be this way as the new universities are almost wholly reliant on central government funding for survival, and we all know how fickle that can be. For the old universities, scholarship is not something that makes money, its something that society spends money on. This difference in emphasis is at the heart of the difference between working in these different kinds of organization.

Universites and politics

It’s a bit dull, but it may help you to understand some of the weird things that happen at universities if you know a bit about the political background. I’m not talking about politics within universities; we’ll have more to say about that rough beast later. This section is about the relationship between universities and central government.

Prior to 1992 there were two kinds of higher education establishment: universities and polytechnics. `Universities’ included a whole range of establishments from the venerable old duffers like Oxford and St. Andrews, to the young, thrusting upstarts like Surrey and Southampton. Although these universities had somewhat different standards, and a different balance between education and research, they were not different in kind, only in — if you’ll pardon the pun — degree. The students were predominantly white, middle-class, of parents who themselves were graduates. `Polytechnics’, on the other hand, were working-class institutions where (and this is a direct quote from a senior politician of the time) `the oinks go to learn plumbing’. Polytechnics were not empowered to award their own degrees; their qualifications were awarded as a group by the Council for National Academic Awards (CNAA) — a body with regulations and structures so byzantine that whole careers were spent trying to understand them. The difference between universities and polytechnics was palpable and plain, at least to the lay person (for which, read `employer’).

All this changed in 1992. At this point Her Majesty (bless ‘er) granted the Royal Charter that made all the existing polytechnics into universities. The reasons for this were many and various, and I won’t go into them here; nevertheless, if the objective was to remove the `second-class’ status of polytechnics and put them on the same level of public respect as universities, it was a failure. Instead, we now have `old universities’ (whose ages range from 20 to 400 years) and `new universities’ (less than ten years old). Despite having the same official status as old universities — and being able to award their own degrees — new universities have exactly the same self-image, and public image, as the polytechnics did ten years ago.

Your mission, should you choose to accept it…

What does a university lecturer do all day? A lecturer’s duties can usually be grouped into three categories: teaching, research, and administration. The balance of time spent on these activities depends on the individual and the institution, but in most places you’ll need to do some of each. It is a goal of most academics to be able to spend most time on research, while minimising teaching and administration. It is a goal of university managers to reduce the amount payed in salaries for support staff. It follows that there is scope for tension here.

Teaching

Most lecturers have to do some of this; historically it was with some reluctance, as teaching was seen as a `second-class’ activity. Why is this? The fact is that in the traditional universities, your prospect of advancement was determined mostly by the prestige which your research commanded. This made sense in a way: you academic peers were able to judge the quality of your research, but the quality of your teaching could only be judged by students. We all knew that students were incapable of mature judgement, and were as likely to rate a lecturer highly because he had an interesting haircut as by the quality of his teaching. So, clearly, students’ opinions were irrelevant.

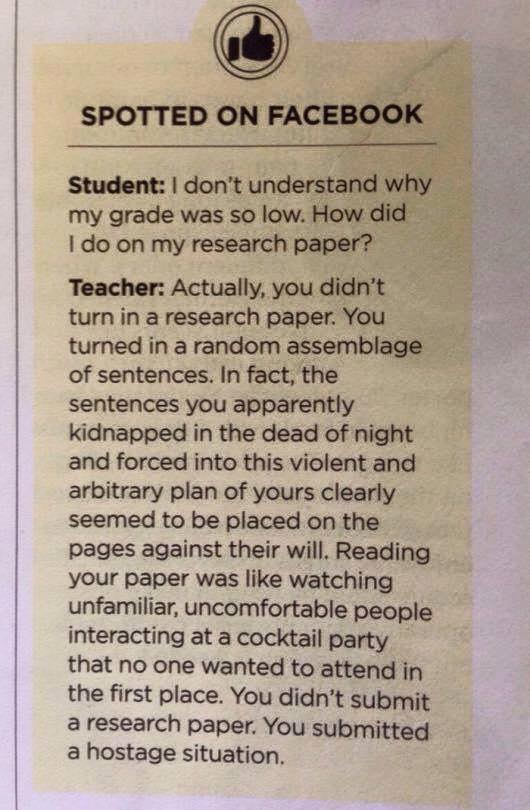

A logical extension of this argument is that if students fail to make progress in a particular class, it is because the subject is more `difficult’ than the students can cope with, not because the teaching is no good.

These days most institutions recognize the value of teaching skills, and being a qualified teacher is more likely to be an advantage in job hunting than it was ten years ago. In addition, many universities run teacher-training programs for their staff, with varying degrees of commitment. As the volume of students admitted to universities increases, the need for competent teaching has increased. Nevertheless, many academics still see teaching as a necessary evil, rather than as a worthwhile and significant activity in its own right. A few years ago I was at a regional meeting of the Association of University Teachers (AUT) where I was told by a lecturer that he had obtained his current job “on the basis of my professional experience, not my teaching abilities”. As near as I can remember, these were his exact words. The inference one was supposed to draw, I imagine, was that teaching was not a `professional’ activity for a lecturer.

Preparation is everything

Teaching — in the sense of delivering lectures, workshops, etc. — is not particularly arduous. In fact, it is the preparation that causes all the problems. If you work in a discipline that changes rapidly, like law or computing, you will find that your classes need frequent updates.

In my current job — in a private-sector training organization — two to three people spend about six months on the preparation of a 5-day (35-hour) course. This includes editorial revisions, quality assurance, testing, and so on. In total this represents about 60 hours of preparation for each hour of delivery. My current employers can justify this expense because courses are taught in a similar format

“We all knew that students were incapable of mature judgement, and were as likely to rate a lecturer highly because he had an interesting haircut as by the quality of his teaching. So, clearly, students’ opinions were irrelevant” world-wide: if a course is taught a thousand times to ten students at a time, at a cost of £1000 per student, then the money raised will easily repay the time spend on preparation.

Universities don’t work like this. Usually a single lecturer will prepare and deliver each course. There is little teamwork or interchange of content between lecturers, and almost none between institutions. Each lecturer `owns’ his course materials, and guards them jealously. This means that the university simply can’t afford to pay the cost of developing first-class teaching materials. If it were to follow the model described above for training in the private sector, where each hour of teaching requires 60 hours of preparation, then a single-term undergraduate course (4 hours contact per week, for 10 weeks) would require 2,400 hours of preparation, or 100 person-days. Obviously the cost per delivery would decrease the more often the course was taught, but in most subjects a course can’t be taught more than a few times before it needs to be revised quite substantially. Course development is, as you can see, an expensive, time-consuming business.

So the unfortunate lecturer has three possibilities when it comes to preparing new courses:

- to accept that it is impossible to do a top-notch job of course development, and do the best that can be done in the time available;

- to use the time that ought to be spent on research or, worse, time that ought to be spent with the family, on preparation of teaching materials;

- to use the same teaching materials year after year.

University academics are naturally fussy and perfectionist, which makes it difficult to accept the first option: doing the best job possible in the time available. Most lecturers either spend far too much time on course preparation or just reuse courses until their slides curl up at the edges.

Teaching methods

Most university teaching takes the same form now that it took 50 years ago: lectures, tutorials, and — in some subjects — hands-on laboratory classes. After nine years in the business I feel I can say quite categorically that lectures are mostly a waste of time for most students. This is particularly true in the newer universities, which recruit less highly motivated students. As these students don’t do any work between classes, the only exposure that they will get to the subject matter is what you tell them in lectures. The idea of standing up for an hour and talking about basic stuff that could just as easily — and much more quickly — be read from a book is something I find quite soul- destroying. At the same time, it is easier to do this than to produce a challenging and thought-provoking lecture that will stimulate students to learn something; moreover, it’s quicker and takes less time out of the all-important research allocation.

Tutorials can be quite effective, if the group sizes are manageable. With large groups you may be able to split the group into smaller units and have them work together instead of directing the class from the front, but this — again — takes time to prepare. A `tutorial’ with 40 students, being directed from the front of the class by the lecturer, is a lecture, whatever you choose to call it.

Hands-on laboratory classes are where the greatest educational gains are to be made, if your subject supports it. Again, recent increases in the number of students in each class have meant that `hands-on’ does not necessarily mean that each student has a hand on. Students frequently have to share equipment and take turns with it. Alternatively, students `work together’ on assignments, which means that one student does the work and the rest goof off.

Undoubtedly the worst teaching-related duty that a lecturer will experience is setting and marking examinations; this is so awful that it merits a section to itself (see below).

Research

Independent research is what motivates most academics. By `independent’ I mean research whose subject and methodology are dictated by the individual lecturer and not by managers or organizational policies. These days, research is only independent to the extent that you can find a funding body to support it; universities have very little in the way of discretionary funding to spend on research. Finding research sponsorship is a skill in its own right, and one that I never really got the hang of. People who do get the hang of it tend to advance rapidly in the academic hierarchy, because everyone likes to see money coming in. Typically, the deal is that you — the academic — will make a case for sponsorship to a particular funding body (e.g., a research council), and then use any resulting funds in a way that you have agreed with the sponsor, not with the university. However, the university will expect to take a chunk of the money (typically 20-40 percent) to cover the cost of housing your equipment and assistants. The larger the funding, the more floor space you will get, and the higher your status will be. You will need floor space and you will need assistants; this is because the process of maintaining adequate funding will leave you no time to do any real research: you will have to delegate it.

Administration

The disapproval which academics feel for teaching undergraduate’s pales into insignificance beside the absolute contempt they have for administration. Depending on the institution, a lecturer’s administrative responsibilities may include matters as mundane as timetabling classroom allocation and organizing the printing of course materials. Timetabling is particularly thankless, particularly as it could be done better and faster by a computer. In fact, it’s far too disheartening to discuss any further.

Part of administration is the attendance of interminable, excruciating meetings. To be sure, some of these meetings are important: these are the ones that are concerned directly with the award of degrees to students. Most of the others are pointless. Scott Adams, the creator of `Dilbert’ has written extensively about the characters found in meetings so I’ve got nothing much to add, except to say that all the personality types he describes — the whinging martyr, the pointless interrupter, etc. — are all represented fully in the academic world as they are in industry.

Now, if academics could all adopt the common-sense approach of Dilbert, and use meetings as a place to practice sleeping with one’s eyes open, things wouldn’t be so bad. But they can’t, for two reasons.

First, academics like to fight. Every decision that is taken in opposition to a particular person’s view is a threat to that person’s status. Second, academics tend to have very strong views on almost everything, regardless of whether they know anything about the subject or not. At meetings of the Computer Science department, it’s fun to throw in a suggestion like: “How about we get rid of Unix systems and use PCs running Windows instead”, and then sit back and watch the others fight like cats in a sack.

Another interesting factor about meetings in the academic world — apart from their duration — is that the balance of time spent on important things and trivial things tends to be distorted. I have seen a major building project disposed of in five minutes, followed by an hour-long discussion of which fonts to use in course handbooks. This is understandable: everyone can have an opinion on typefaces, but building contracts are incomprehensible.

Students

Students represent the lecturer’s greatest reward and heaviest burden. Some students can be both at the same time. There can be few more gratifying experiences than to instil a life-long love of learning into another human soul, or to hone a blunt, dull-edged mind into an analytical instrument of surgical precision. Most lecturers experience this once or twice in their careers. For the rest of the time, we take averagely bright individuals with modest critical faculties, and do what we can to turn them into averagely bright, but well-educated, individuals with some notion of independent thought.

The brain drain

For most academics, it is fun to teach students that are exceptionally smart and capable. There are some lecturers who derive satisfaction from helping the less gifted to achieve their full potential but this — although admirable — is rare. Generally smarter students respond better to instruction and require les s of it, so you win both ways.

The problem is that few lecturers are fortunate enough to work in a university where all the students are budding Einstein’s. In almost all institutions you will hear the following observations reported:

- every year, more students have to be taught by the same number of academics;

- every year, the average level of academic capability of students is lower than the year before.

Now, we have to be a bit careful here. I can imagine Socrates complaining to Plato that Athenian youths weren’t as bright as they had been in his day. In fact, whining about the declining intellectual capacities of students is a favourite pastime of all teachers; they just can’t help themselves.

So with that warning out of the way, allow me to perpetuate the noble tradition of student-bashing in my own way. It seems to me to be a matter of fact, not of conjecture, that if the number of people of a given age in higher education increases, then the average intelligence of the student body must decrease. This observation is roundly rejected by central government, and disparaged — at least in public – by senior university administrators. But, as I said, it’s a matter of plain fact. However, we choose to measure human intelligence, whether it be on an IQ scale or otherwise, there will be a concentration of measurements in the region of some central point. For IQ, that centre is at about 100 IQ points. This is not a coincidence: IQ is defined such that it averages to 100 points. Now, there will be some people with IQs higher than this, and some lower. The number of people with IQs over 140 will be smaller than the number between 130 and 140. This number will in turn be smaller than the number between 120 and 130. The number of people with IQs between 100 and 110 points will even larger. And so on. This is simply a matter of empirical observation. If we admit more eighteen-year-olds to universities, will we be admitting more people with IQs in the 120+ range, or in the 100-120 range? The fact is that people with IQs of 120+ have always had a university education. We can’t get more of these people into university, because they are all there anyway. If we wish to have more people in higher education, then we have no option but to admit less able students; it’s just a matter of arithmetic.

Now, I’m not suggesting for a moment that people of ordinary levels of intellectual capacity should be denied an opportunity to be educated to their full potential. Far from it. But, if we as a society make a decision to do this — and we have — and we choose to use the medium of the existing university structure to do it, then we must accept that the average intellectual capacity of students will decline. Again, no problem in itself. The problems start to arise when people claim that universities can educate to objectively-defined, stable standards despite the decline in the average ability of the student. This is clearly impossible, and one of the greatest sources of stress for university lecturers.

Here are some other comments often heard about students from lecturers.

- “Students are lazy: they don’t do anything outside class”. Students are only lazy compared to university lecturers, who tend to be driven by their inner demons. For a lecturer to say that a student is lazy is like a giraffe criticising a horse for having a short neck. Actually many students are very industrious: they are all working outside class to pay their tuition fees. When I was an undergraduate most students could expect at least a modicum of financial support from the state; this has now all but disappeared. An increasing number of students have to work not merely part- time, but full-time.

- “Students are illiterate”. Again, as many academics think that misusing an apostrophe merits the death penalty, the standard of comparison may be invalid. In fact, university students write as they speak, as do most people. The problem is that most people have no formal training in writing skills by the time they get to university. This is hardly the fault of students; if you are the kind of person that finds tortured grammar offensive, seek alternative employment.

- “Students have poor numeracy”. Everyone has poor numeracy. The ability to think around problems in numerical terms is a special skill that takes most people years of continuous practice to acquire. I can assure you from experience that well-educated professional people are no more numerate on average than undergraduates.

- “Students leave everything until the last minute”. See above. University lecturers tend to be well-organized and logical, and have learned the hard way how to make optimal use of time. Everybody else puts off doing disagreeable tasks as long as possible.

That sinking feeling

I heard a rumour that doctors use the abbreviation `HSP’ on a patient’s medical records to indicate to other doctors that the patient is likely to be a bit of a trial. `HSP’ stands for `heart-sink patient’. As a university lecturer you will encounter the related phenomenon of the `heart-sink student’. There are certain students in every department that the lecturers dread dealing with. Not, usually, because these people are abusive or threatening, or even particularly demanding. On the contrary: some HSSs — as I shall call them — are the nicest people you could hope to meet. HSSs usually earn their status in one of the following two ways (sometimes in both).

- The first type of HSS — the less emotionally draining — is the person who is incapable of finding things out. However clearly you think you have explained something in a class; however thoroughly you have analysed a problem; however monosyllabic your presentation: the HSS will be there after class — every class — seeking further clarification. This student will not always be a person of less-than-average academic prowess, although this is sometimes the case. More often, the HSS is a person who has no confidence in his or her intellectual faculties, and needs constantly to be reassured. The problem is that this student does not seem to be able to make use of the information sources that are available when tackling a problematic subject area. Most students will exercise a degree of initiative, and seek answers from books, Web sites, and other students. The HSS simply registers incomprehension and then sets off to find the lecturer. In the most intractable cases the HSS will require everything to be explained repeatedly before being satisfied.

- The second type of HSS is much more of a problem. This is a student who develops an unhealthy dependency on a lecturer as a result of emotional problems. As a lecturer, you must remember that many students are young and a long way from home (particularly in these days of increased intake of students from overseas). `Home’ in this case need not be merely a geographical location: many overseas students are cut off from their cultures and social support structures as well as from their geographical homes. The phenomenon is not necessarily more prevalent in students who are furthest from home: I never noticed it among Chinese students, for example. The reason, I think, is that some ethnic and cultural groups are strongly represented in universities, and their members are able to form their own support networks. Similarly, in North London there are large populations of people of Greek, Turkish, African and Indian ethnicity. Students who could identify with these cultural groups also were rarely a problem. On the other hand, students from cultures that were under-represented were much more likely to turn into HSSs. In my experience the most emotionally troubled students were from the Middle East, the USA and Australia. These were all nationalities that had few students in each faculty.

This type of HSS manifests deep insecurity and loneliness. He, or she, may try to meet the lecturer several times a day. He may follow the lecturer from classes, and seek opportunities to prolong a conversation. He may — and frequently does — seek out courses taught by a particular lecturer, to the detriment of academic balance. When alone with the lecturer, the student may well be tearful and sullen, while appearing bright and cheerful in public.

None of this is particularly dramatic, but such behaviour is not characteristic of a professional relationship between mature adults.

Most universities now have counselling services to help students with emotional problems, but I always found it difficult to tell students that they needed this kind of intervention. This is bad, because prompt counselling may avert problems before they become serious. `My’ HSSs were mostly harmless, but I have encountered behaviour that borders on what might be called `stalking’ these days. It’s rare, but it does happen. Occasionally the police have to be involved. Slightly more common, and just as worrying, are students who attempt to commit suicide in the presence of their lecturers. On one occasion I had to restrain a student physically who attempted to jump out of a window while shouting “I’m gonna do it! I’m gonna kill myself…!” Almost the saddest part of this event was that the window in question was only six feet above ground level.

It’s important to be able to distinguish the student who is exhibiting a healthy reaction to awful events, from one who is emotionally disturbed. In my time as a lecturer I encountered students who faced appalling personal circumstances: families killed in wars, serious illnesses, and financial privations, among other things. These students either dealt with the problems and carried on, or left the university. The HSS, on the other hand, never deals with whatever problems he has, and continues to be a drain on anyone who shows any sympathy.

Although a university lecturer will have to deal with many students whom it is unrewarding and exhausting to teach, I want to stress that real heart-sink students are very rare. An increasingly important skill for a lecturer — one that I never really mastered — is the ability to maintain a professional distance from the emotional turmoil’s of your students. You will have your own stresses to deal with. If you show any willingness to engage with these students’ problems at a personal level, many others like them will seek you out and destroy you. This is why it is increasingly common for university planners to put lecturer’s offices into a part of the building that is secluded from outside access. When I first started teaching in universities, any student who wanted to see me could stroll up to my office. By the time I left, my office was in a part of the building that was protected by two security doors. All this, of course, increases the sense of isolation and lack of support that students feel.

Examinations

Exams are a key feature in the life of a university student, and an even bigger feature in the life of a lecturer. In some organizations, activities associated with examinations can absorb 50% of a lecturer’s time.

Students are often surprised to learn that examinations are often set in advance of the preparation of the course being taught. This is necessary because the procedures for getting an examination through the various stages of a approval and quality control are so complicated. In addition, as most universities offer students the opportunity to re-sit examinations they have failed, it’s common to have to set a re-sit paper as well as the main paper. An individual lecturer will probably be responsible for examining two to four courses in each term, and if we assume there are six questions on each paper, that means that you will have to write 24 exam questions — and marking guides and model answers — in total each term. It’s therefore a good idea to start early.

If setting exams is a chore, marking exams is a nightmare. I frequently had three classes with over a

hundred students in each, and where each class would have an exam paper which required four questions to be answered. That’s a total of 100 * 3 * 4 = 1,200 exam questions in each teaching session. Then, if 10 percent of these students failed and had to re-sit (which wasn’t unusual), there would be a further 120 questions. That’s an awful lot of marking, however you look at it. The university would sometimes provide assistance by contracting part-time lecturers for marking duties, but this caused further problems in reconciling the marking standards adopted by different individuals; frequently this was more trouble than it saved.

Moderation in all things

After the nightmare of marking, we have the living hell of moderation. `Moderation’ is, in principle, the process of ensuring that marking is fair and consistent. The real purpose of moderation is to fool auditing bodies into thinking that there is some kind of procedure to the examination process. Committees can spend hours debating the relative merits of `blind double marking’, `open double marking’, and so on; in practice, however, no-one has the time to indulge in these activities so it is necessary to give the illusion that they have been done. A typical strategy is to select samples of students’ papers for double-marking. No-one knows how big the sample sizes should be, or what level of statistical accuracy is to be achieved, or how to deal with discrepancies in the marks awarded, so organizations are free to implement this scheme as they see fit. There is no evidence that they are efficacious, or that they serve any purpose other than increasing the workload of the already burdened academics, but they do keep the auditors happy, which is the main thing.

Happily, it is increasingly realized that true moderation is impossible, and lecturers can club together the form `moderation rings’, in which everyone moderates the work of his friends and colleagues. This is much less hassle that doing the job properly, and is indistinguishable to all but the most cynical administrator.

External moderation is a different matter: the moderator won’t usually have a close working relationship with the moderate, so is less reticent in being critical of examination standards. Usually external moderation is put forward as a way to ensure that different institutions adopt comparable standards. In practice, moderators have to work to the moderated institution’s own standards — at least to a degree — or be driven mad by the contradictions involved.

Stress

There is an impression among university graduates that don’t themselves work in universities (i.e., most of them) that the life of a lecturer is idyll of academic indolence. The very word `lecturer’ conjures up images of stuffed armchairs in oak-panelled studies, strolling over the lawns discussing the deconstruction of post-modern verse, and spending a couple of hours a week giving the same lecture as last year, and as the year before.

Does this sound like an agreeable working life? It certainly does to many would-be academics. What about this instead: an article in the Guardian last year (June 12, 2001) reported that 88% of lecturers claimed to have suffered from stress-related health problems, ranging from high blood pressure to strokes and alcoholism. Does this sound like an agreeable working life?

I have become convinced that the continued existence of universities is predicated on this simple fact:

lecturers would rather work themselves into an early grave, rather than fail to meet their perceived obligations to their students or to scholarship. The entire system hinges on this being true; if it weren’t, then university education would cease.

So what are the specific causes of stress?

Long working hours. A survey by the NATFHE union in 1998 reported that over a quarter of lecturers routinely worked more than 55 hours a week. I found myself that 70-80 working weeks were not that uncommon. Various explanations have been advanced for the existence of this excessive workload, but the cause is irrelevant; it’s the brute fact that’s important to the individual lecturer.

- Erosion of the distinction between home life and work life. The same survey reported a “striking” spill-over from the workplace to the home. One of the most insidious problems in university work is that much of it is open-ended. Only your professional pride dictates when jobs are finished to your satisfaction. Because many tasks have no well-defined deliverables, it becomes very tempting to take home some `light’ work which won’t interfere too much with family life (reading a conference paper, for example). So your workplace has entered your house. Now, once you’ve accepted that the boundary between work and home has been broken, it becomes natural for `home’ to be the place where you finish off all the stuff you can’t finish at `work’. Because there are immense pressures to teach more courses to more students, your working day can easily be full of student-related activities. Where are you going to do your administration, research, background reading, and grant applications? At home, that’s where.

- Perceived low value of the work. Much of the work that lecturers are increasingly being asked to do is perceived to be of `low value’. To an academic `low value’ work is anything that doesn’t advance scholarship, or doesn’t seem to. This includes activities like accounting for how one spends one’s time, dealing with disputes between students and staff, timetabling classes, writing `mission statements’, and conforming to institutional standards for document preparation and the like. Whether these things really do advance scholarship indirectly is a matter that could be argued either way, but ultimately lecturers aren’t interested in this sort of thing, and resent being compelled to do such work.

- Cognitive dissonance. This can be defined simply as the effect of trying to reconcile beliefs or values that are irreconcilable. For example, lecturers like to believe that they are upholding and furthering objective standards of scholarship. Moreover, they think they know what those standards are. At the same time, they believe on the basis of observation that the intellectual prowess of students entering universities is, on average, declining. If these beliefs are true reflections of fact, then the average numbers of students failing, of failing to complete, university courses should be increasing more rapidly that it currently is. Something simply doesn’t add up here.

Academic politics

“Academic politics is the most vicious and bitter form of politics, because the stakes are so low.” — Wallace Sayre

While captains of industry manipulate each other and the people around them for big bonuses, stock options, and fat retirement funds, academics will cheerfully sabotage each other’s careers for the right to sit in the big, comfortable chair at meetings. In fact, even the most senior academics probably earn as much money as a computer programmer in the private sector with a few years’ experience. So what is it that motivates these people?

Status

Lecturers are not motivated by the same things as other people — money and power — but by the desire to be acknowledged as an expert in a chosen field. This is an academic’s measure of status.

To be acknowledged as an authority, the academic will need to have a large number of students and assistants to do all the real work, and have a large amount of space to house them in. As a lecturer’s fortunes rise and fall over time, his floor area will grow and shrink. If the floor area becomes large enough, a highly motivated lecturer can make a bid to take over a department. This is particularly true in institutions where heads of departments are chosen from the academic staff by consensus, rather than by administrators. In other words, a lecturer’s status, recognition, and floor area are inextricably linked.

Now, as discussed above, a lecturer’s recognition by his students is irrelevant because students’ opinions are held to be worthless. What matters is recognition by other lecturers. This means that status is tied to research activity above all else, as it is something that other lecturers can relate to. No lecturer increases his status by being a renowned teacher.

Status is everything

Considering how meagre their achievements usually are in terms of the impact they have on the world, it may be surprising how arrogant and self-satisfied many lecturers are. This is explicable on that basis that a lecturer’s status is based on his or her recognition as an expert, so it does not help to show any uncertainty or intellectual weakness. In addition, since we can’t have an profession in which every member is at the top of the tree, so to speak, an individual’s status can only increase if another’s decreases. This explains why academics spend so much time rubbishing each other’s work.

Class

The British class system is alive and well in British universities. Some are worse than others, of course; older institutions tend to be the worst culprits, but not always. Class manifests itself in the segregation of different categories of staff and student.

The `upper class’, if you will, are the senior academics: professors and deans. These people have reached a level where they don’t have to do any real work at all: they just coordinate other people’s efforts. The `upper middle class’ comprises the full-time lecturers, the main body of the academic staff. The `lower middle class’ are the research students and research assistants. Note that all these people have some research interests, and this puts them into the middle class. The `working classes are the technicians, part-time lecturers, and administrators. These people don’t do any research, and therefore have no measurable expertise. Thus they are doomed to be an underclass. Note that research students occupy a more exalted position than technical staff, even though earn no money and have no real responsibilities. This is a further manifestation of the finding that status is governed by research.

Until as recently as a few years ago, a sort of apartheid existed between the `middle class’ academics and `working class’ administrators and technicians in many universities. They had separate washrooms, separate catering facilities, and different types of contract. Moves to break down the class barriers were often met with hostility — on both sides. To be fair, academic staff and administrative staff frequently found that they had very little in common, so this isn’t entirely surprising. In fact, academics typically have very little in common with anyone except other academics.

Getting in and staying in

Let’s suppose that, having read the above and, remaining undeterred, you still hanker for the groves of academe. How does one go about becoming a lecturer? There are, essentially, three ways in, which I call the `front door’, the `back door’, and the `trap door’.

The front door

To enter the academic profession by the front door is to follow the approved, socially acceptable, route. It is also the hardest, least remunerative, and the least likely to succeed. However, if you do succeed this way then you will likely continue to succeed, because all the people that succeeded in front of you succeeded the same way, and academics, as we know, like people like themselves.

The traditional route into an academic career is to study for a good first degree, then a PhD, then to gain experience as a post-doctoral research associate for a few years. You will then be in a position to apply for the most junior of academic jobs. By this point you will probably be about 30 years old, hold at least two good degrees, have worked in a professional capacity for several years, and be earning about the same as a recent graduate (According to the Guardian (July 15, 2002) the average starting salary for a university graduate, over the whole of the UK and in all sectors is £19,600. National pay scales set entry-level university lecturer salaries at £20,000-26,000). Even if this appeals, there are two major problems.

- You must be able to survive as a post-doctoral researcher for an unspecified length of time. In London you will earn (according to the Association of University Teachers) approximately the same as trainee driver of Underground trains with 5 GCSEs (about £18,000). However, the trainee driver will be 16, you’ll be at least 24, and that’s assuming that you’ve done nothing but study for your whole life.

- Even if you have adequate qualifications and experience, competition for junior academic positions in reputable institutions is intense. There are far fewer openings than there are people. What this means is that you’ll have to continue to take successive short-term contracts to support yourself, while frantically applying for every decent permanent position going.

While I was a PhD student I worked alongside people who were in their late 30’s, and had been contract researchers their whole working lives. Many of them had the same responsibilities as lecturers (and were called `honorary lecturers’), but without any form of job security.

It’s been argued that this way of life is a good preparation for the rigours of an academic career, in the same way that it is argued that working 70-hour shifts is good training for junior doctors. It is certainly true that this `front door’ approach is probably the only way into the more prestigious universities at present.

The back door

Many universities have a `back door’ recruitment policy that works in the interests of practicality. The back door may admit people, for example, from outside the academic world who have particular skills that the institution needs. While a university would be loath to pay a living wage to a 30-year-old PhD graduate with five years’ experience as a research assistant, it may be prepared to be more generous to a person of the same age from the industrial sector. Remember that a university is going to want to recruit through the front door if it can, and the only reason it will relax this policy is if it can’t get staff of decent calibre this way. We have already seen that competition for entry to good universities is quite intense, so it follows that back-door recruitment is most likely to be effective for less prestigious institutions. An exception is that even the most respected universities may admit non-academic captains of industry into the professorial ranks; at that level of seniority contacts and reputation are more important than academic prowess anyway.

To enter the academic profession through the back door you don’t always need a PhD, but it helps.

On the whole, back-door recruits have a harder time of things than front-door recruits. This is because they tend to have fewer contacts in the academic world, and have less experience at raising research funding.

The trap door

I use the term `trap door’ for methods of entering the profession which are indirect. On the whole, these methods are now defunct, but if you work in the academic sector you are likely to encounter trap-door people, so it’s as well to recognize them, as they have a totally different outlook on life to that of academics who have entered the profession the hard way.

One method of becoming a university lecturer is to get a job as a lecturer in a college of higher education that is seeking to become a university. When the institution changes status, you will change with it. This happened en masse in 1992, of course, when all polytechnic lecturers became — for better or worse — university lecturers. Many of these people were, and still are, admirable lecturers. Some failed to adapt to the changed emphasis and left the profession, often into secondary and further education. Others cling doggedly on, despite being academic outclassed by the new intake of junior lecturers. Many of these people are quite senior, and well payed. This is a cause of chagrin for recently- appointed, highly qualified young academics. Why, they argue, should a person with a PhD and a proven track record in research earn less money than an ex-polytechnic lecturer who does half as much work and is far less skilled? Bad luck, that’s why.

Another short-cut for the budding academic is to get a part-time post as a lecturer, or a short-term contract, and become indispensable. Competition for part-time and short-term lectureships is far less intense, so recruitment is more relaxed. If you are good at the job it will be much cheaper for the university to continue to renew your contract every time it expires than to recruit someone else. Eventually, you will have amassed enough working time to be in a position to take legal action against your employer for wrongful dismissal if it fails to renew your contract when it expires. You can then insist on being offered a full-time and/or permanent contract when the university wishes to recruit new staff. This tactic can be very effective.

On the whole, people who join the academic profession in ways like this are accorded less respect from their peers than people who do it the hard way.

Those who can: do; those who can’t: teach

To conclude, here are some tips that I couldn’t follow myself. If I had followed them, perhaps I would still be a lecturer. But I doubt it: I like to be able to pay the mortgage every month.

- Your time is limited: the work isn’t. Academic work is open-ended; however much you do, there will always be more that could be done. Even if you could work 24 hours a day the mountain of work that needs to be done will still tower over the molehill of work actually finished.

- Never take work home. Not ever, not even once, however inoffensive it seems. Taking home, a research paper to read is the thin end of the wedge that has staying up all night marking exams at the thick end. The absolute worst that can happen if you follow my advice is that you’ll get fired. The worst that can happen if you don’t is that you’ll die. In my last job two of my colleagues attempted suicide as a result of the stress of the work. Two others needed psychiatric treatment. Keep a sense of proportion.

- Don’t take a personal interest in students’ well-being. There are just too many of them, and only one of you. Find who is responsible for dealing with students’ non-academic problems and be ready to delegate pastoral responsibilities.

- Don’t expect students to be as hard-working, smart or well-organized as you are. This will only lead to disappointment. Remember that students have totally different motivating factors to lecturers.

- Maintain employable skills. For most academics, the idea of getting an `ordinary’ job, where you have a boss and wear a suit, is unthinkable. However, it reduces stress if you know that you could find alternative ways of making a living if you had to.

- Don’t evince any technical skills to your colleagues. It is handy to have some (see above) but you should keep them to yourself. First, if you are good at, say, fixing computer problems, people will keep asking your help. Second, technical matters are `working class’ to academics, however skilled they may be, and will lower your status.

Conclusion

A university professor of my acquaintance retired recently, after 40 years’ service. His comment on his long and distinguished career merits quoting: “I think that, on the whole, the benefits of an academic career are largely illusory”. Yet people continue to want to make their livings this way, despite the difficulty of entering the profession and the stress of remaining in it. These people are generally skilled and highly employable, and could make much easier and more remunerative lives for themselves. Why do they do it? The fact is that fewer and fewer people are doing it: people are leaving the academic world at a greater rate now than has been the case for many years. On the negative side, unless you’re very senior, salaries are uncompetitive even with unskilled occupations, and the long hours and stress can’t be good for general health. On the positive side, being a lecturer gives a strong sense of public service, of working towards a higher goal than mere personal enrichment. This, no doubt, is a significant motivator for public-spirited people.

Credit for writing this very long essay goes to: http://www.kevinboone.com

This article is part of Community Care’s Stand up for Social Work campaign. We’re standing up for social work by being honest, offering support and providing inspiration.

This article is part of Community Care’s Stand up for Social Work campaign. We’re standing up for social work by being honest, offering support and providing inspiration.

From the point of view that on-line learning is an additional method and in many ways a very rewarding way of delivering quality education. The trend in educational institutes is to move towards a more flexible student-orientated approach. The tradition way and more economical way of piling large numbers of students into a lecture theatre are, at last, being seen as not the most suitable way of creating a quality student learning environment. It is time-consuming to develop on-line material and can be expensive but research proves that students prefer a method where they can explore in more detail area that has caught their imagination. My experience has been that to create multimedia interactive learning material, which can also be applied to on-line learning, is very time-consuming. I am now of the opinion that it may be a better approach to source funding for the project then employ a specialist to create the material. The role of the lecturer then becomes one of a manager, in that they will be responsible still for the delivery and content but will be free of the burden of training oneself to initially create the material. Although I am a firm believer that on-line learning can enhance student learning, as is suggested by the student feedback it is still important to consider the problems that may be encountered. On-line learning is not automatically a vehicle for productive and effective learning. All sorts of fascinating usually inappropriate things easily sidetrack students, this results in them staying well away from the intended learning outcome.

From the point of view that on-line learning is an additional method and in many ways a very rewarding way of delivering quality education. The trend in educational institutes is to move towards a more flexible student-orientated approach. The tradition way and more economical way of piling large numbers of students into a lecture theatre are, at last, being seen as not the most suitable way of creating a quality student learning environment. It is time-consuming to develop on-line material and can be expensive but research proves that students prefer a method where they can explore in more detail area that has caught their imagination. My experience has been that to create multimedia interactive learning material, which can also be applied to on-line learning, is very time-consuming. I am now of the opinion that it may be a better approach to source funding for the project then employ a specialist to create the material. The role of the lecturer then becomes one of a manager, in that they will be responsible still for the delivery and content but will be free of the burden of training oneself to initially create the material. Although I am a firm believer that on-line learning can enhance student learning, as is suggested by the student feedback it is still important to consider the problems that may be encountered. On-line learning is not automatically a vehicle for productive and effective learning. All sorts of fascinating usually inappropriate things easily sidetrack students, this results in them staying well away from the intended learning outcome.